“…respectfully request for a pardon of six hours a day for the purpose of exercising in New Orleans” wrote Lt Henry M McClendon as a prisoner in the U. S. Customs House in New Orleans. A neighbor to my 2xgreatgrandUncle George M. Hill. both men had been captured, Henry on Nov 22, 1863 at Camp Pratt, LA a place known more for training soldiers. George at the siege and battles at Port Hudson, May 23-July 9, 1863. Henry’s brother Thomas was married to George’s sister Margaret. Long-time neighbors in Texas the men joined the Confederacy together in August of 1861. The McClendon brothers survived and returned to Texas. George died at the Custom House four months after capture.

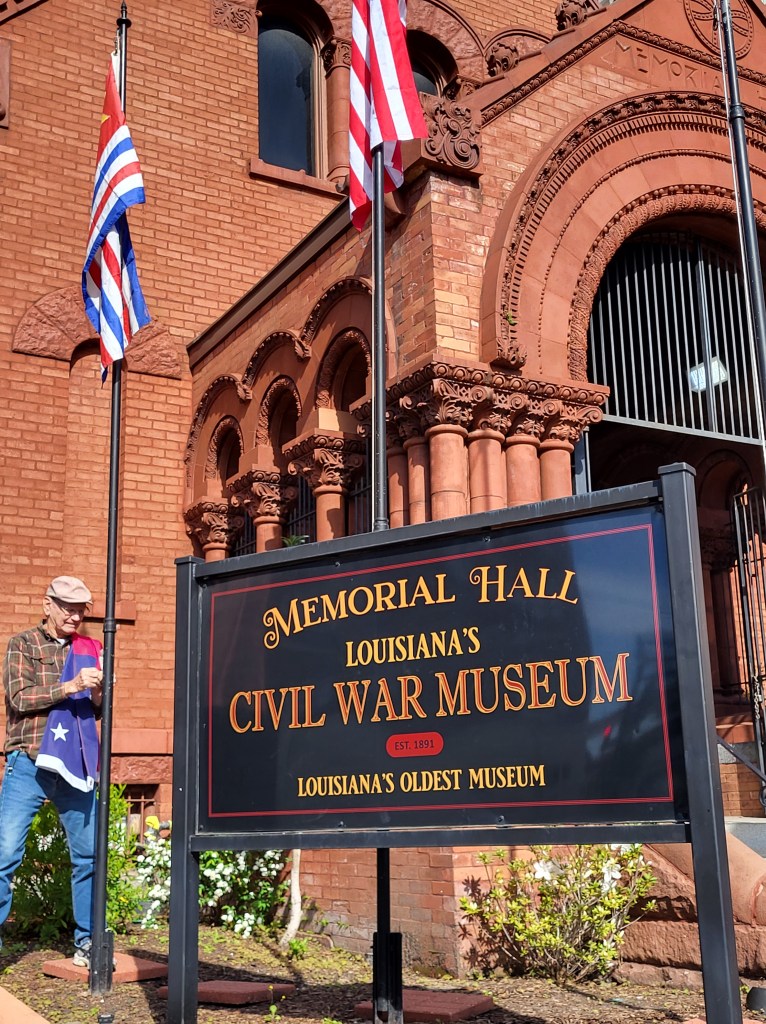

I’ve left 10 days of wandering about Louisiana’s many sites of Civil War skirmishes and formal engagements (see prior blogs) to get a bed in a hotel room. Time to explore the The Home of the New Orleans Confederate Museum – Confederate Museum, U.S. Customs House, and Cypress Grove, Metairie, and Greenwood Cemeteries. I have dead people to find. And etouffee.

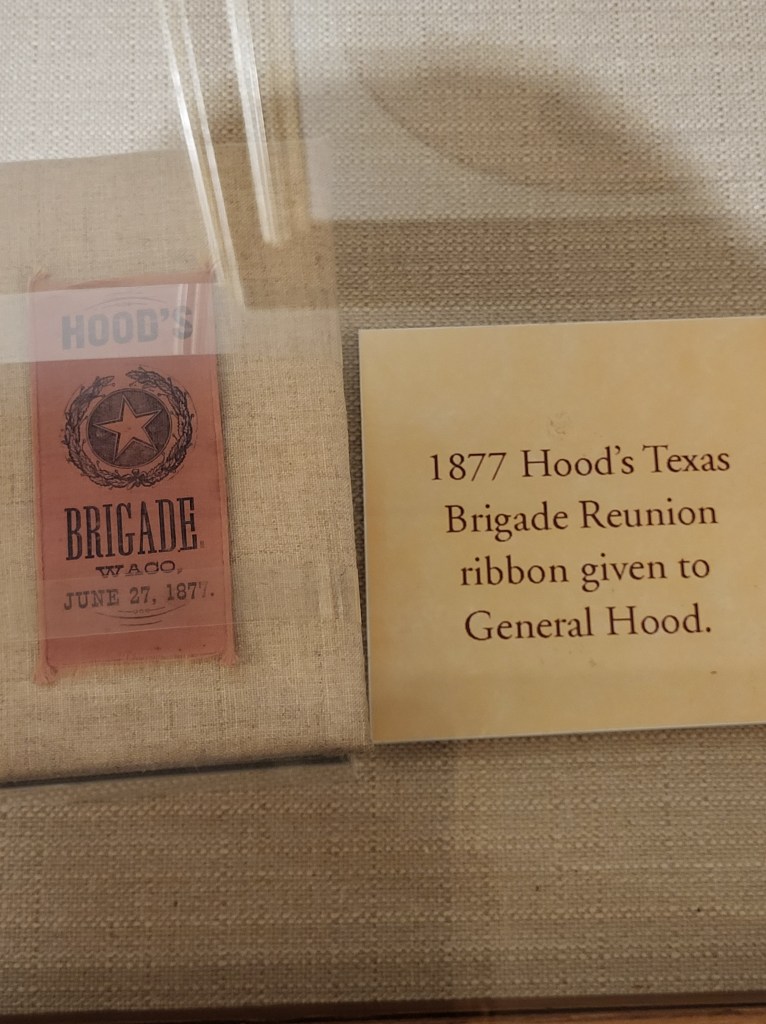

I enjoyed the small but well curated Museum, especially the exhibit on Civil War Period Photography. Excellent explanation and visuals on the difference between ambrotype, tintype, daguerreotype, stereo, Carate de Visite, and Cabinet Card. Who knew? They also had original portraits and information of Gen John Bell Hood, who eventually replaced Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston until his aggressive leadership of the Confederacy may have resulted in more soldier deaths than necessary. He led several battles outside of Louisiana that I’ll be visiting as my Ancestors fought under him. Hood returned to New Orleans after the war to make money in cotton. Unfortunately, the Yellow Fever epidemic in the winter of 1878-79 took his business, wife, oldest child and him. He left 10 orphans. The Museum also has exhibits that list what gear a Cavalry or Infantry man might carry, and artifacts of their gear.

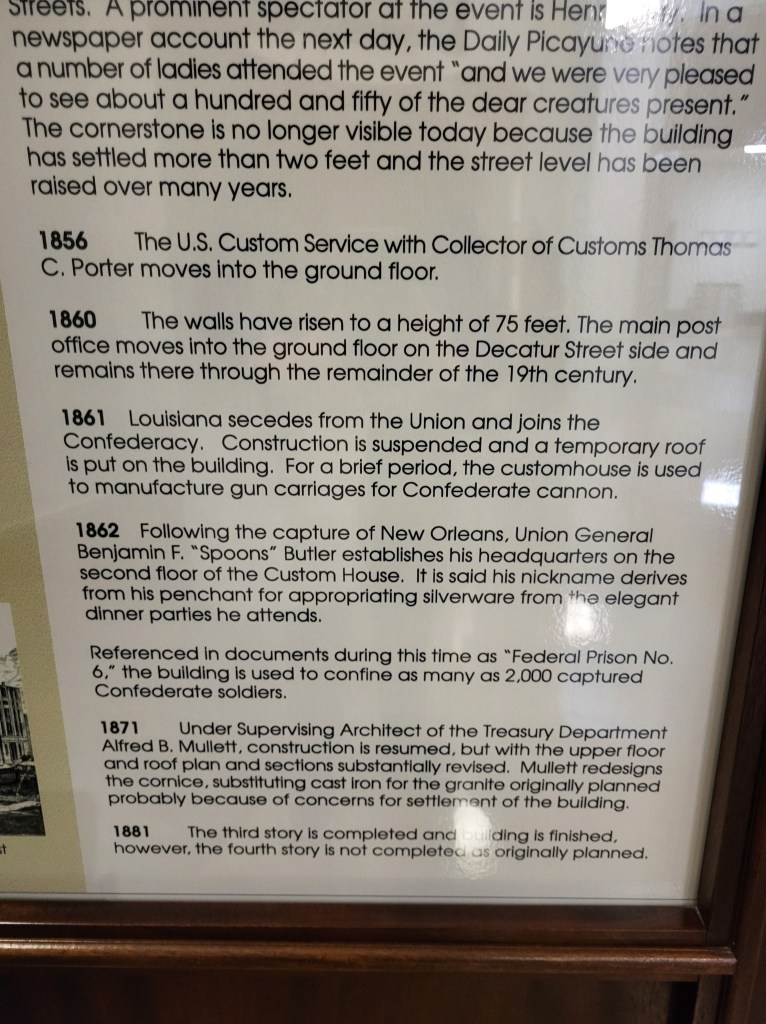

After the Museum, I decided to “take my exercise” down Canal Street to the magnificent Federal U.S. Custom House. Time to discover the first of many POW camps I’ll visit on my travels. I already knew that there was a bit of history about the building inside. Searching for the public entrance I asked the man standing outside for help. As it turned out, Officer William Lynch was happy to tell me that there was information inside about the building. He led the way; I emptied my pockets and was scanned. As I signed in, he observed that I listed Talkeetna Alaska as my home address. Just like that, one of the many enjoyable moments of travel occurred: making a new friend. He was in the military in Anchorage for four years in the late 1980s.

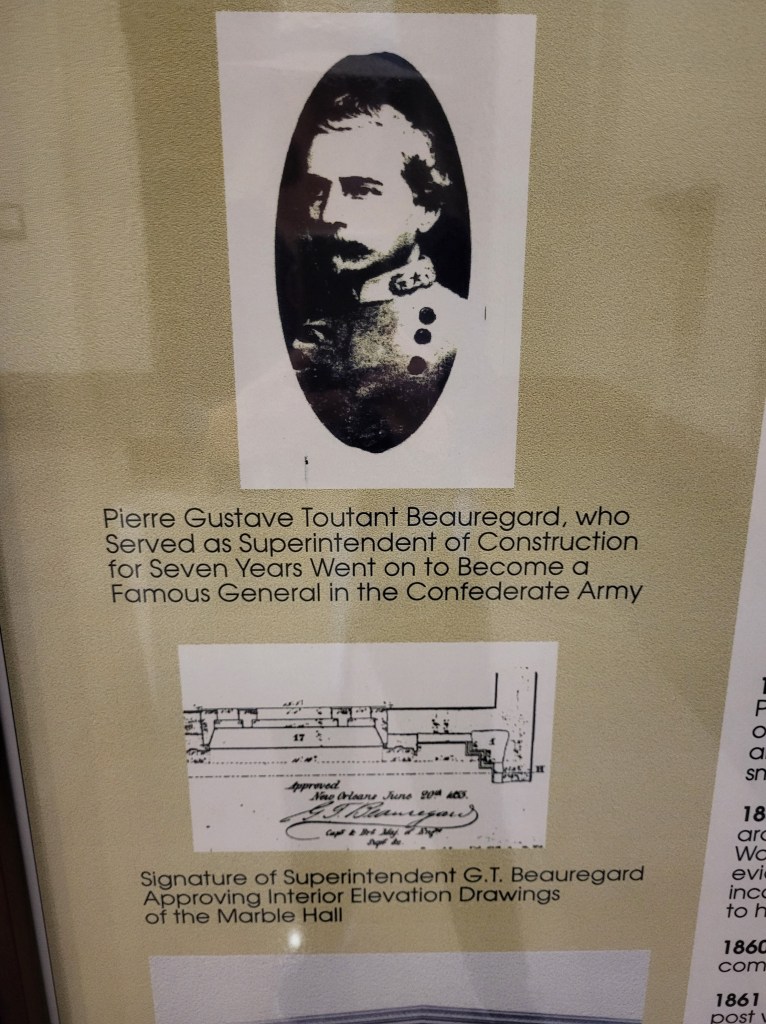

Once inside I found the additional proof that up to 2000 prisoners were held in the Custom House, known as “Federal Prison No. 6.” I also learned that Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, better know as P. G. T. Beauregard gave up his role as Superintendent of Construction for that as Confederate General.

William and his co-workers told me I could catch a trolly to the cemeteries at the end of Canal Street.

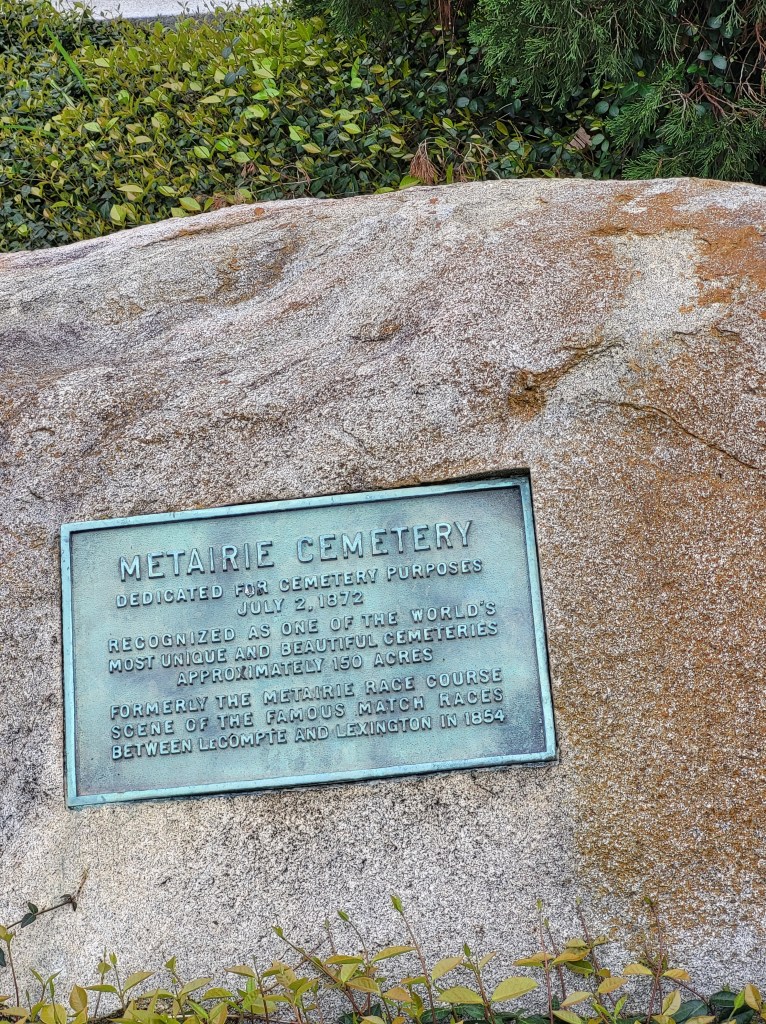

Most visitors to New Orleans take a cemetery tour. I prefer doing it alone, as I enjoy being lost. The houses for the dead are remarkable in their beauty and solidity. At the time Cypress Grove, Greenwood, OddFellows, and a quarter a mile on the opposite side of Interstate 10, Metairie were established cheek-to-jowl at the dead end of Canal Street this area was far from the excitement of the port city of New Orleans. This was a place to bury those who had died from the frequent yellow, typhoid and other fevers and diseases quite common to the heat and humidity and filth of the 1850-1880s. Metairie Cemetery was a former racecourse before switching use to a cemetery in 1872.

I was interested in Metairie Cemetery because the majority of my Civil War Confederates served under General Albert Sidney Johnston (who died early on at Shilo). I knew a statue of him atop his horse Fire-eater would make finding the Confederate section easy for me. I was not disappointed, as I walked under Interstate 10, climbed around the barrier, and walked in.

With the roar of Interstate 10 over Johnston’s shoulder I contemplated the lives and decisions the men of the Army of the Tennessee, Louisiana Division made. I’m learning in my exploration that where my guys fought this division did also. Beauregard, who assumed command in the initial hours after Johnston was killed is buried here. Gen Richard Taylor (son of President Zachory Taylor) who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Theatre where the majority of my Texas ancestors fought hard to resist Nathanial Bank’s push in the Red River Campaign to acquire Texas is also here. Johnston’s remains didn’t stay long. The Texas Legislature in January 1867 had his remains transferred for burial in the State Cemetery in Austin. In 1905 the Elisabet Ney, my favorite sculptor created a stone monument of him lying in repose. While beautiful, I like the one here better.

I knew that George wasn’t buried in any of these lovely cemeteries. I couldn’t safely get a photo that also includes the Canal Street sign, but the trolly helps capture the sense of place. As I drank my coffee and watched through the window at the traffic moving down Canal Street, past the well-know places of rest I think of him, and others found in the mass grave adjacent to Greenwood Cemetry many years ago. So many bodies, victims of fevers that can fell a strong person within hours leaving them as they were, paving over them for time immemorial seems a good choice.

Leave a comment