“Rats, of which there were plenty about the deserted camps, were also caught by many officers and men, and were found to be quite a luxury–superior, in the opinion of those who eat them, to spring chicken,” wrote Howard C Wright, a New Orleans newspaperman and current soldier in the 30th Louisiana Infantry a couple of months after enduring the 48-day (May 21-July 9, 1863) siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana. The seige also included two of Maj General Nathaniel P. Banks’ ( May 27 and June 14) assaults against the four-and-a-half-mile string of fortifications protecting the Mississippi River.

I learned at the Museum exhibits, and from Dane a most-helpful employee, that Wright, along with my 2nd great-uncle George M. Hill and a 2nd cousin, 4th removed (we share the same Progenitor Philip Fry, Revolutionary Soldier) found themselves unable to leave Port Hudson. I’m not certain how much of the almost-a-year of work in preparing the Confederate batteries for this strategic position high (80″ bluffs) above the sharp curve in the Mississippi River they did. Thousands of soldiers and dozens of Units were on site from Alabama, Mississippi, Tennesse, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. But I do know they didn’t leave before or during the two assaults (water and land) from the Union’s attempt to control the River. They were among the 6800 troops who faced 30,000 Union troops on May 23 when the siege began.

I spent a few hours walking the grounds. I discovered the ravines–many 60′ deep–and streams that made it difficult for Infantry.

May through early July 1863 was a series of wins for the Union–Vicksburg, Gettysburg, and now Port Hudson in Louisiana. At Port Hudson and Vicksburg the Union troops were unable to turn back the Confederates with several costly battles. So they resorted to siege, a proven war tactic dating back to 3000 BC in Egypt. A day after learning that the Confederate leaders at Vicksburg gave in, so did Port Hudson. The Union now had control of the entire Mississippi River.

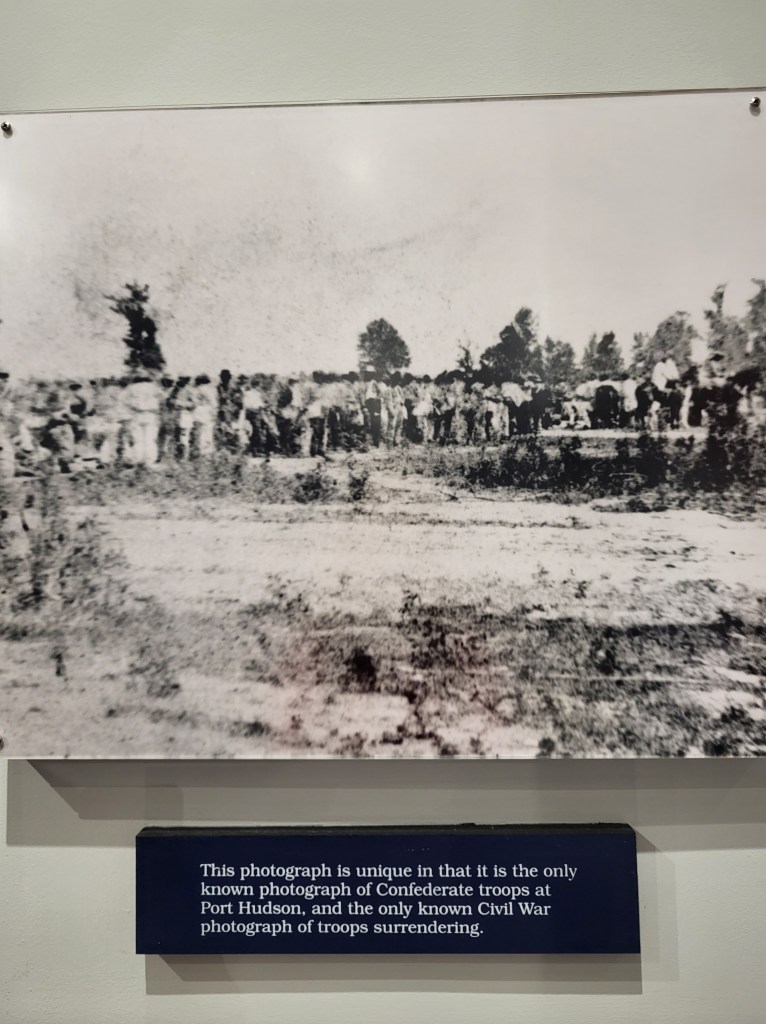

If I knew what George looked like, he might be in this photo.

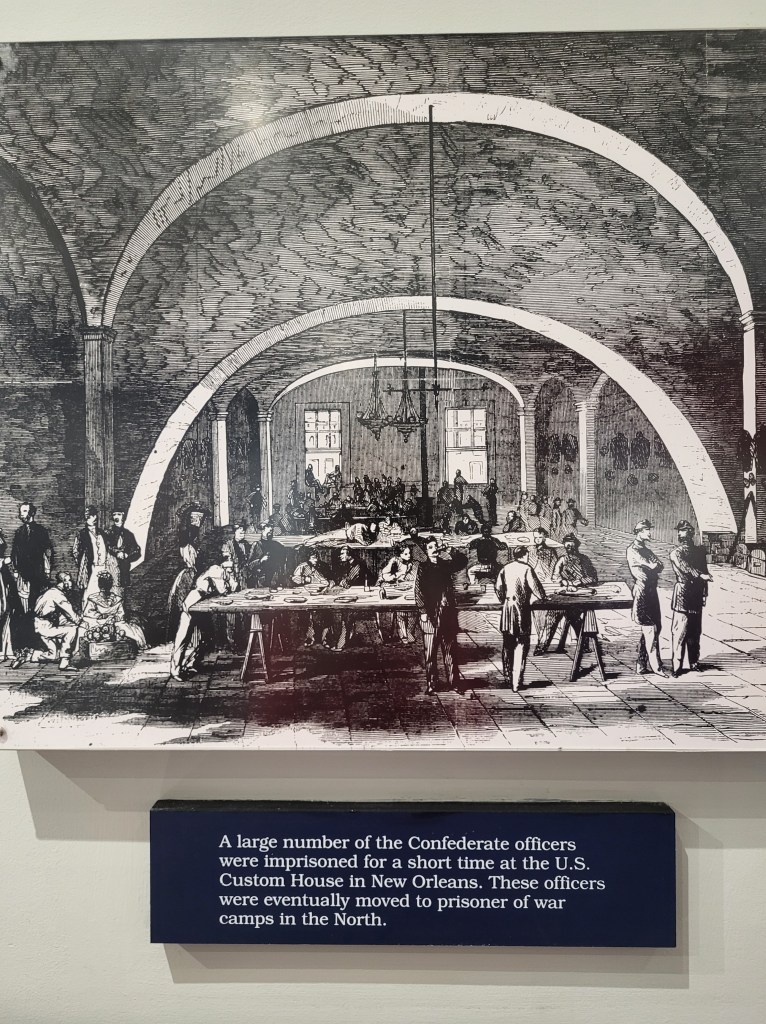

George M. Hill, was captured and sent with other officers, including Wright, to the New Orleans Custom House, currently branded as: “Federal Prison #6.”

Wright lived to write about “Port Hudson from the inside”, (see link below.) George died four months later of typhoid fever on Oct 31, 1863. He was buried a handful of miles along Canal Street, what was then “outside of town” in a mass grave with other victims of the fever. This field-of-dead was discovered several decades ago when digging to extend Canal St to where Greenwood, Cypress Grove, Oddfellows, and a quarter of a mile on the opposite side of Interstate 10, Metairie Cemeteries stand. These cemeteries do have Confederate and Union solders and officers buried here. But not George who was likely considered contagious even in death. Basically, he is buried under Canal Street, near Morning Call Coffee Stand. His remains were not sent to other cemeteries, they were paved over.

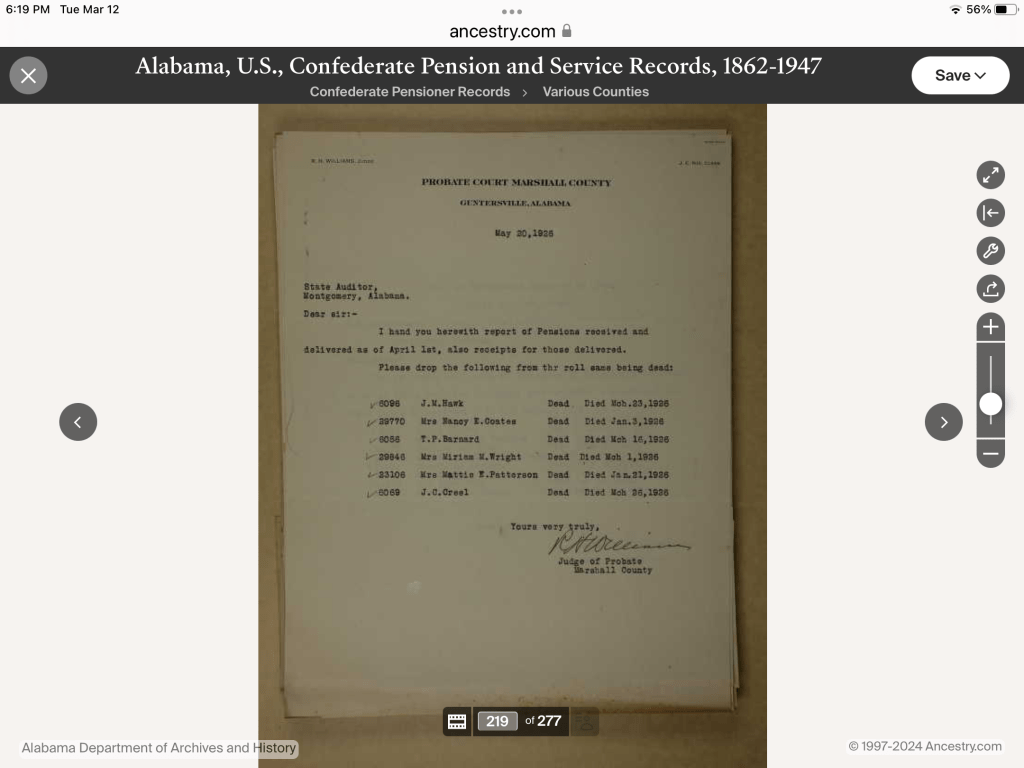

Private Timothy P. Barnard, of the 49th Alabama infantry, my 2nd cousin 4th removed (we share the same Progenitor Philip Fry, Revolutionary Soldier) was exchanged on the spot at Port Hudson. Confederate Timothy lived to fight another day–until the very end of the war. Remarkably, he drew a pension until 1926 when at age 83 he died where he lived his entire life, near Fry Gap, Alabama.

I encourage you to stop at Port Hudson, and other Civil War and Nature-centered sites in the area. I’ve added links for more information..

Port Hudson Battle Facts and Summary | American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org)

Leave a comment